Donald Trump said during the election campaign that he wanted make it easier to win a libel suit, that he planned to sue The New York Times for libel and would sue women who accused him of sexual assault.

President-elect Trump has seemed to pull back from the threats, possibly because all of those vows would be hard to accomplish.

The reason is New York Times v. Sullivan, one of the greatest victories for free speech and a free press. The decision makes it hard for public officials to win libel suits.

Even if Congress were to pass a law to make it easier for public officials to win, the law would be unconstitutional because it would violate Sullivan and the First Amendment.

What is lost in the mists of time is that the decision was as much about the Civil Rights Movement as the press.

The Supreme Court’s aim was to protect the northern press from ruinous libel judgments in the South, aimed at forcing the northern press to look away while police turned dogs and high-powered fire hoses on children and other demonstrators.

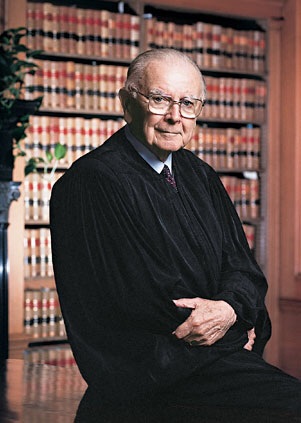

Justice William J. Brennan Jr., the intellectual leader of the liberal Warren Court, said that public officials would have to show “actual malice” to win in court. Democracy needed to provide the press with the breathing room to make mistakes.

“We consider this case,” wrote Brennan, “against the background of a profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust and wide-open, and that it may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials…Erroneous statement is inevitable in free debate, and (it) must be protected if the freedoms of expression are to have the ‘breathing space’ they ‘need to survive.’”

King in the courtroom

The case was argued on Jan. 6, 1964 with the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in the courtroom. On the day of the oral argument, Justice Arthur Goldberg sent down to Rev. King a copy of the civil rights leader’s book of the Montgomery bus boycott – “Stride Toward Freedom” – asking for an autograph.

The oral argument was sandwiched between two other momentous events. Five months earlier, in the summer of 1963, Dr. King had led the huge March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The largest crowd in United States history marched on the National Mall.

Five months after the oral argument, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The Sullivan case had begun with a mistake-riddled full-page advertisement in The New York Times with the title “Heed Their Rising Voice.”

The ad had been placed by southern ministers leading the civil rights movement and by noted entertainers such as Harry Belafonte, Sidney Poitier and Marlon Brando and celebrities such as Jackie Robinson and Eleanor Roosevelt.

The ad contained several mistakes. Most were minor. Dr. King had been arrested four, not seven times. Students demonstrators were not singing “My Country ‘Tis of Thee’; they were singing the National Anthem.

Students were expelled by the State Board of Education but not for leading the demonstration at the Capitol but rather for demanding service at a lunch counter in the Montgomery County Courthouse on a different day. Most of the student body, not the entire student body, protested the expulsion. They did it by boycotting class, not refusing to re-register. The biggest mistake was the claim that armed police had ringed student protesters at Alabama State and padlocked their dorm to “starve them into submission.” The dorm had not been surrounded nor were the officials trying to starve the students.

The New York Times advertising department made no effort to check the facts, instead relying on the good name of civil rights leader A. Philip Randolph, who vouched for the signatures on the ad. Had the Times checked its own morgue, it could have discovered the errors.

Almost no one read the ad in Alabama. Only about 394 copies of the editorial circulated in the state, about 35 of which were distributed in Montgomery County where L. B. Sullivan was the police commissioner. Sullivan was not named in the ad, a fact that became important.

The person who noticed the ad and got the controversy stirred up was himself a journalist, Grover C. Hall Jr., editorial editor of the Birmingham Advertiser. Hall wrote an editorial condemning the ad under the headline: “Lies, lies, lies.”

Hall himself opposed segregation and was the son of a Birmingham Advertiser editor who won the Pulitzer Prize for opposing the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s. But Hall Jr. thought that northern pressure caused pushback from the South. He also was irritated that the northerners turned a blind eye to racism in their own backyards.

The trial

The judge’s handling of Sullivan’s lawsuit against the Times was infected by segregationist bias. First, the Times had trouble finding a lawyer who would represent it in Alabama. Then the trial judge, Walter Berman Jones, denied the Times’ efforts to remove the case to federal court, even though that ruling was contrary to legal treatise on the subject of jurisdiction that Jones himself had written.

The 100th anniversary of the Confederacy fell during the trial, and Jones allowed the jurors to wear Confederate uniforms and pistols to court to commemorate the occasion. The jury returned a verdict of $500,000, a large sum at the time.

Nor was the verdict the only one that the Times faced in the South. Harrison Salisbury, the legendary Times reporter and editor, estimated that the Times faced about $3 million in libel and criminal libel judgments in the South, all flowing from civil rights coverage. Justice Hugo Black noted that the Times had 11 libel suits against it in Alabama alone, seeking a total of $5.6 million. CBS faced another $1.7 million, he noted.

This situation came at a time when the nation’s leading newspaper was financially vulnerable, as it recovered from a financially damaging strike. George Freeman, a former New York Times lawyer, recalled that the advertising side of the Times argued in favor of the paper pulling out of the South editorially because of the financial threat of the libel suits.

Brennan addressed the issue of self-censorship in his opinion. “Whether or not a newspaper can survive a succession of such judgments, the pall of fear and timidity imposed upon those who would give voice to public criticism is an atmosphere in which the First Amendment freedoms cannot (survive)…A rule compelling a critic of official conduct to guarantee the truth of all his factual assertions – and to do so on pain of libel judgments virtually unlimited in amount – leads to…self-censorship.”

The rationale

Brennan gave several reasons for providing more protection for speech critical of public officials than private individuals. One was that American history demonstrates that the First Amendment does not permit seditious libel for criticizing the government.

Brennan corrected an old wrong. He noted that the Sedition Act of 1798 made it a crime punishable by prison and steep fines to criticize public officials, including the president, then John Adams. The law was used to jail newspaper editors who supported Adams’ political opponent, Thomas Jefferson.

Brennan noted that the Sedition Act never had been tested in the Supreme Court. The controversy preceded the establishment of judicial review in the 1803 Marbury v. Madison decision. But Brennan said that the “attack upon the Sedition Act’s validity has carried the day in the court of history” and that “its invalidity has been assumed” by the justices of the Supreme Court.

Brennan went on to note that a judgment of the size involved in Sullivan case could be a greater punishment than meted out the 1798 Sedition Act. Because the 1798 law violates the First Amendment, then state libel laws that punish criticism of public officials even more harshly must also violate the amendment.

Another reason for removing some libel protection from public officials was it would put public officials on a level playing field with citizen critics. The court already had recognized that statements made by public officials criticizing private citizens could not be libelous unless made with actual malice.

Finally, the court ruled that Sullivan could not collect because he was not named in the ad.

Chief Justice Earl Warren had chosen Brennan to write the opinion because he was the mostly likely justice to win over the entire court. Brennan was known as a schmoozer who excelled at creating majorities and sometimes unanimous opinions. Brennan succeeded in the Sullivan case when Justice John Harlan withdrew his dissent at the last moment.

In 1967, soon after Sullivan, the court extended the actual malice standard to public figures.

Fight to preserve Sullivan

When Trump made his criticisms of the libel law, most of the public commentary supported Sullivan. But it has not always been that way.

The decision faced severe challenges in the 1970s and 1980s on the court and society. Lee Levine, a noted First Amendment lawyer, recalled that “there definitely was a time and place when Brennan was afraid Sullivan was at risk.”

During the 1980s two big national libel suits by two generals left media lawyers wondering how much protection Sullivan provided. Gen. William Westmoreland sued CBS for its stories criticizing the general’s conduct of the Vietnam War. Israeli Gen. Ariel Sharon sued Time magazine for its stories about his involvement in the Israeli killing of Palestinian refugees in camps in Lebanon during the Israeli invasion. Both lawsuits were wars of attrition that involved huge defense costs and damaged the credibility of the media involved.

The challenge within the court was more serious. The Progeny, a book published on the 50th anniversary of the decision, described Brennan’s successful effort to nurture and save Sullivan. The book is written by Levine and Steve Wermiel, the former Wall Street Journal Supreme Court correspondent who conducted extensive interviews with Brennan before the justice’s death.

The book injects an ironic footnote to history: There was a marked difference between the public Brennan who believed passionately in the press and the private Brennan who had an uncomfortable relationship with the press.

Brennan didn’t think the press did a good job of reporting on legal issues because reports on the Supreme Court lacked depth. Nor did the press respect people’s privacy, he said. The press coverage of Justice Abe

Fortas that led to his resignation hurt Brennan.

But on the court, Brennan continued his all-out effort to defend Sullivan against former allies and new conservative opponents.

Justice Byron R. White, who had joined him in Sullivan, soon served notice he did not entirely buy into the decision. He had been on board in Sullivan partly because of the civil rights backdrop. White had been President John F. Kennedy’s assistant attorney general for civil rights.

Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist also expressed doubts and narrowed the reach of Sullivan in a case involving an opinion column written by an Ohio sports columnist.

Mike Milkovich was a legendary wrestling coach at Maple Heights High School in Ohio. His squads often won the state title. During one big wrestling meet, a fight broke out between communities. Milkovich denied instigating the fight when he testified under oath to a hearing of state education officials.

Sports columnist Ted Diadiun wrote that, “Anyone who attended the meet…knows in his heart that Milkovich…lied at the hearing after…having given his solemn oath to tell the truth.” Milkovich sued.

Up to this point the court had said in some of its libel decisions that there was no such thing as a false opinion. That had led many libel lawyers to assume that statements of opinion were immune from libel suits. That assumption turned out to be off base.

In Milkovich v. Lorain Journal Co., in 1990 Rehnquist said the court had not actually meant that there is no such thing as a false opinion. In some instances, opinions appear to be based on the assertion of particular facts; if a news organization has shown reckless disregard of the truth of those facts, then a statement of opinion can be libelous.

Media lawyers were surprised and mildly panicked. But the Milkovich decision didn’t have as much impact as it first seemed it might.

Parody for the first time

Even though Rehnquist once had appeared to be a threat to Sullivan he ended up expanding Sullivan in an important decision involving parody – Hustler Magazine v. Falwell in 1988.

The Rev. Jerry Falwell was a nationally prominent and politically influential preacher who frequently provided important support to conservative candidates and causes.

Larry Flynt, the publisher of pornographic Hustler Magazine, printed an ad parody patterned after the Campari liquor advertising campaign in which celebrities talked about their “first times.” Although the ad suggested through double entendre that the celebrities were talking about the first time they had sex, the ads actually talked about the first time that had drunk Campari. The Hustler parody said that Falwell’s first time having sex was with his mother in an outhouse when they were both drunk. It also said Falwell only preached when he was drunk. A label in small type at the bottom of the ad read: “Ad parody – not to be taken seriously.”

Falwell sued for emotional distress and had home court advantage in Virginia where won a $150,000 judgment against Hustler for infliction of emotional stress.

What few people knew about Rehnquist was that he had once been an avid, amateur cartoonist in his days at Stanford University. One of the influential amicus briefs was filed by the nation’s editorial cartoonists. They pointed out that exaggeration, parody, sarcasm and hyperbole were their bread and butter.

One cartoon that the lawyer preparing the brief left out was drawn when Rehnquist was in the midst of a difficult confirmation fight. That one showed Rehnquist in Ku Klux Klan robes trying to deny blacks the right to vote in his native Arizona. The cartoon played off of Rehnquist’s controversial role as a young Republican election judge challenging the voting credentials of African-Americans.

The chief justice cited the cartoonists’ brief in writing about the long history of hyperbolic political cartoons dating back to the cartoons that ridiculed Boss Tweed during the Tammany Hall corruption of the 19th century.

“The political cartoon is a weapon of attack, of scorn and ridicule and satire;” he wrote. “it is least effective when it tries to pat some politician on the back. It is usually as welcome as a bee sting, and is always controversial in some quarters…

“Despite their sometimes caustic nature, from the early cartoon portraying George Washington as an ass down to the present day, graphic depictions and satirical cartoons have played a prominent role in public and political debate…From the viewpoint of history, it is clear that our political discourse would have been considerably poorer without them.”

Rehnquist conceded “there is no doubt that the caricature of (Falwell) and his mother published in Hustler is at best a distant cousin of the political cartoons described above, and a rather poor relation at that. If it were possible by laying down a principled standard to separate the one from the other, public discourse would probably suffer little or no harm. But we doubt that there is any such standard, and we are quite sure that the pejorative description “outrageous” does not supply one.”

Rehnquist extended the Sullivan actual malice standard to parody and other hyperbolic speech. It is a somewhat unusual application of a standard that requires knowledge of falsity. The Hustler ad was published with the knowledge that the claim of having sex with his mother in an outhouse was actually false.

Wermiel, the Progency author says Brennan was ecstatic with Rehnquist’s opinion. “Rehnquist…wrote an opinion that Brennan could have written. Brennan said the press should just kiss Rehnquist for his opinion in Hustler v. Falwell. He could leave the court in peace. If Rehnquist could write that opinion, New York Times v. Sullivan was safe.”

Two million people libeling all day

To most First Amendment advocates, New York Times v. Sullivan is a touchstone of press freedom. Without it, timid editors would pull their punches and self-censor to avoid costly libel suits. Public officials would use libel as a way to bludgeon media with the temerity to portray them in an unfavorable light – the way that public officials and public figures use defamation in Great Britain.

But even First Amendment advocates are squeamish about the no-holds-barred environment of the Internet.

“I wonder if there is libel any more,” said former New York Times lawyer James Goodale on the 50th anniversary of Sullivan. Sullivan – together with Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act governing online defamation – have resulted in “egregious examples of outrageous libel,” he said. “…You have two million people libeling each other all day long.”

Section 230 is a law that gives online computer services immunity for suit based on third party postings on their sites. So, if a poster defames a person on Facebook, the victim can sue the poster but not Facebook.

Geoffrey Stone, a noted First Amendment expert and professor at the University of Chicago Law School, said Brennan was “thinking about mainstream, professional reporters.” Now, with the Internet, “people engaged in professional discourse… are not professional at all…Instead of dealing with professional reporters it now includes every Tom, Dick and Harry on the Internet…

“One can make the argument that the long-term consequence of Sullivan is to destroy credibility and that has a damaging impact on democracy…Sullivan was situation driven – it was about the Civil Rights Movement, not the First Amendment…But as a First Amendment decision it left a lot of the justices uncomfortable…Its consequences for public discourse became much more problematic…False statements don’t advance public discourse…they poison discourse.”

Because of New York Times v. Sullivan, the law is more protective of free expression than are the ethical codes of major news organizations. The decision can protect poor, careless, unethical reporting that violates journalistic norms.

Ethicists have advocated national or regional news councils. The council is composed of retired judges, journalists, lawyers and other notables. Under this approach, the panel of notables hears evidence from both an aggrieved official and from the editors and reporters. The aggrieved party agrees in advance not to seek money damages.

But news councils never have caught on. The Minnesota News Council, one of the most prominent, disbanded several years ago.

Twibel – 64 characters of trouble

Sullivan was decided in the pre-Twitter world. So what about a 140-character tweet?

Mark Sableman, of Thompson Coburn in St. Louis, answered that question on his Internet Law Twists &Turns blog this year. “Even those tiny 140-character-limited messages known as tweets can lead to full-fledged litigation, subject to the same full and painstaking linguistic and legal scrutiny as any other case,” he wrote.

In fact, it only took 64 characters to get the iPad newspaper app The Daily in trouble. News Corp.’s supposedly trend-setting new newspaper reported on a 2012 fight at the Manhattan nightclub, WIP. Rappers Chris Brown and Drake and their friends got into a fight over singer Rihanna.

Under the headline “Ri-Ri’s Rumble,” the Paper gave an account of the brawl that included a tweet by a DJ Rashad Hayes: “I was gonna start shooting in the air but I decided against it.”

Hayes’ whole tweet had read: “I was gonna start shooting in the air but I decided against it. Too much violence in the hip hop community.”

Hayes claimed that the shortened tweet made it look like he was present, when he was not, and that he was trigger-happy. This harmed him because he lost a job at the nightclub and other clubs thought he would talk to the press.

A New York appeals court said Hayes could potentially make a case that he was damaged because it appeared he was present and ready to shoot. Meanwhile, The Paper was not so trend-setting as News Corp. thought. It went out of business in 2012.

No Comments