Americans think today about how important the First Amendment is to the Constitution and our lives as the freest people on earth. So it may be surprising the First Amendment lay dormant for the entire 18th century until coming to life 100 years ago.

It was World War I. Americans were scared by the war, immigrants and the Russian Revolution. President Woodrow Wilson roiled against hyphenated Americans — Germans and Irish and southern Europeans. He said they “poured the poison of disloyalty into the very arteries of our national life.”

His Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, whose Chevy Chase, Maryland, house was bombed in 1919, ordered raids against leftists, anarchists and immigrants. His new head of the Bureau of Investigations, J. Edgar Hoover, led the raids.

Congress passed the broadly worded Espionage Act 99 years ago. It is with us still. Chelsea (Bradley) Manning of WikiLeaks fame was convicted under the Espionage Act. Edward Snowden is charged with violating the law.

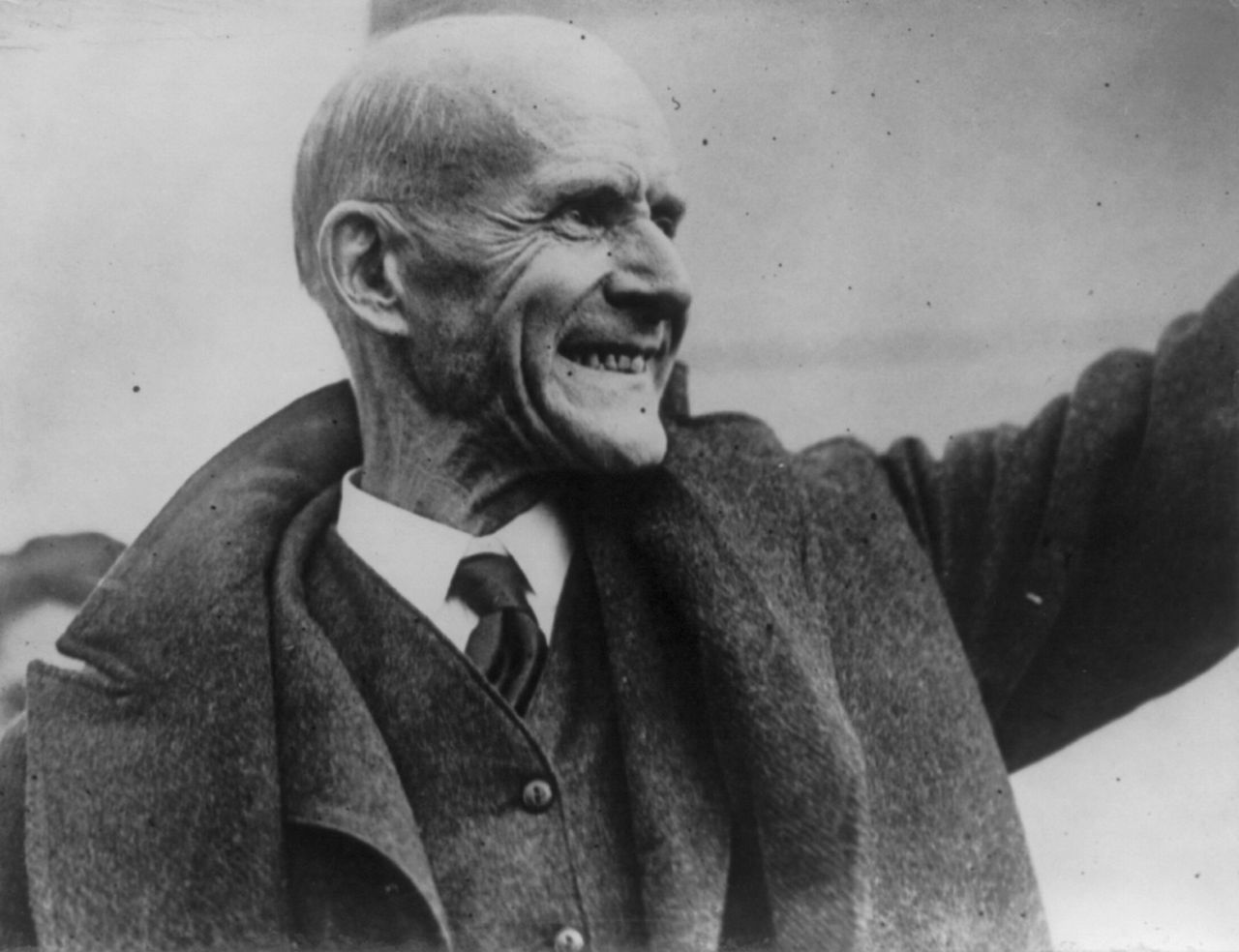

During World War I, anti-draft and anti-war activists were arrested and jailed for violating the Espionage Act and its amendments on sedition. Eugene Debs, the Socialist Party candidate for president, was imprisoned for his Ohio speech likening the draft to slavery.

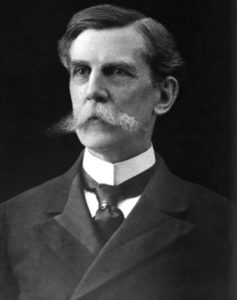

The Supreme Court of the United States overturned none of those prison sentences, all of which would be unconstitutional today. But two of the most famous justices on the court, Oliver Wendell Holmes and Louis Brandeis, began to dissent from the rulings putting the protesters in jail.

These were the first stirrings of the First Amendment. Holmes put it this way in his 1919 dissent from a decision affirming the conviction of five Russian immigrants who criticized the United States for opposing the Russian Revolution. Holmes said in Abrams v. U.S.:

“…when men have realized that time has upset many fighting faiths, they may come to believe even more than they believe the very foundations of their own conduct that the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas – that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market….”

It took many more decades before most Supreme Court justices agreed.

In the beginning

When the Founding Fathers — they were all men — wrote the Constitution they didn’t include a Bill of Rights.

They went to Philadelphia worried about too much democracy in the years after the American Revolution War. They wanted stability.

The first proposal for a Bill of Rights was defeated at the Constitutional Convention in August 1787. Then In September, one week before the end of the convention, George Mason of Virginia said it would “give great quiet to the people” if a Bill of Rights prefaced the Constitution. Mason had written Virginia’s Declaration of Rights.

But Roger Sherman of Connecticut thought the bills of rights in eight states were enough protection and Mason’s proposal was defeated. Two days later Charles Pinckney of South Carolina tried to add a provision guaranteeing liberty of the press, but Sherman blocked that proposal too.

On the last day of debate, Mason announced he wouldn’t sign the Constitution. He explained, “There is no declaration of any kind, for preserving the liberty of the press, or trial by jury in civil cases; nor against the danger of standing armies in time of peace.”

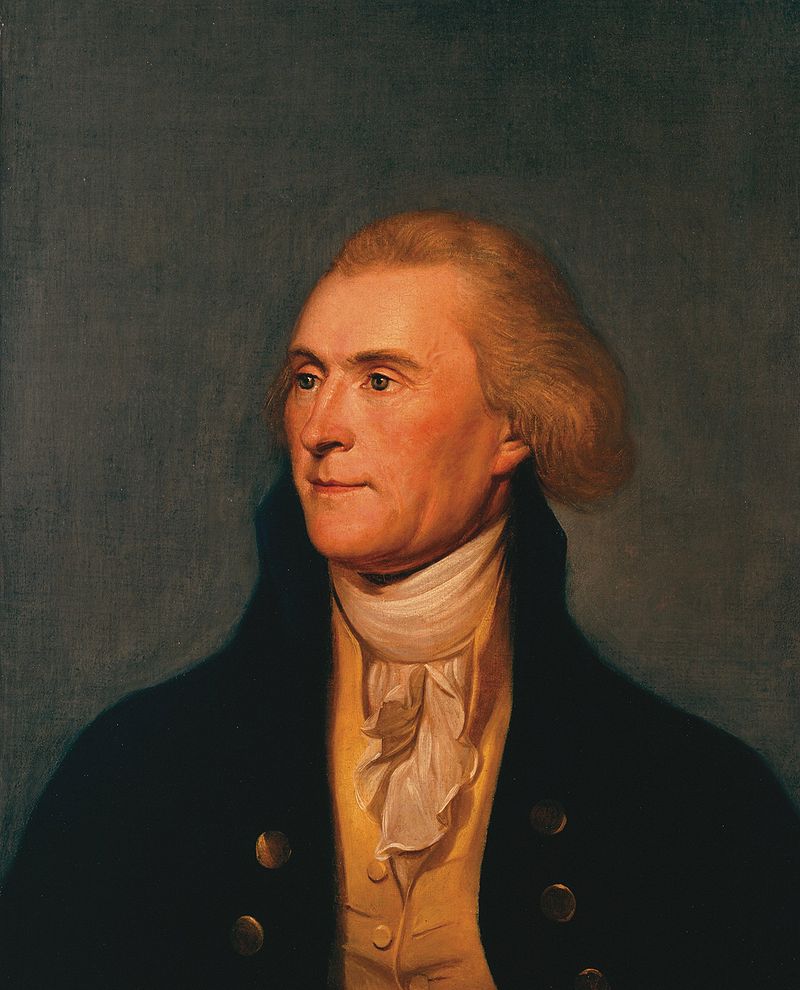

At that time Thomas Jefferson was in France. He wrote Madison that he supported the Constitution, but added, “what I do not like, first the omission of a bill of rights…. A bill of rights is what the people are entitled to against every government on earth, general or particular & what no just government should refuse or rest on inference.”

Alexander Hamilton disagreed. In Federalist Paper 84 — one of the essays supporting ratification of the Constitution — Hamilton said the entire Constitution should be seen as a bill of rights because of its checks and balances and federalism. “The people surrender nothing; and as they retain everything they have no need of particular reservations.”

Hamilton said the push for a bill of rights amounted to “frighten(ing) the people with ideal bugbears.”

George Washington thought the push for a bill of rights was a smokescreen for those trying to block ratification. He stayed home from the Virginia ratifying convention. That left Patrick Henry, the fiery orator, as the most famous Virginian at the convention.

“Perhaps an invincible attachment to the dearest rights of man may, in these refined, enlightened days, be deemed old-fashioned,” he said. If so, he said he preferred to be considered an “old fashioned fellow.”

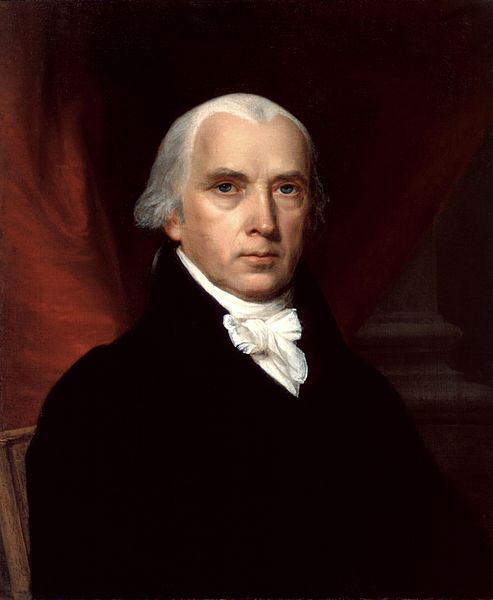

Madison, who later wrote the Bill of Rights, was opposed at the Virginia ratifying convention. He called a bill of rights “unnecessary and dangerous – unnecessary, because it was evident that the general government had not power but what was given it… dangerous because an enumeration which is incomplete is not safe.”

But Henry prevailed and the Federalists agreed to call upon Congress to pass amendments as soon as possible. With that assurance, Virginia ratified the Constitution 89 to 79.

Madison agreed to write the Bill of Rights, calling it his “nauseous project.” He went ahead because he thought it would blunt the efforts of four states to call for a new constitutional convention.

Madison’s sparse and elegant prose states the rights in a legally enforceable way, something that became important in the hands of a independent judiciary that took on the role to interpret what the Constitution means. For example, the First Amendment begins, “Congress shall make no law….”

The rights are all negative rights protecting the people from the government, not positive rights that require the government providing food, housing or education to the people.

Madison was a short man with a small voice. He was barely audible when he proposed the Bill of Rights in Congress in 1789.

He explained the main purpose for the document was to guard “against the legislative (branch), for it is the most powerful, and most likely to be abused.” He added that the bill would guard against abuses by the “body of the people, operating by the majority against them minority.” And he included a thought he had borrowed from Jefferson – that “Independent tribunals of justice will consider themselves…the guardians of those rights; they will be an impenetrable bulwark against every assumption of power.”

Congress removed some of Madison’s flourishes, such as he statement that freedom of speech and the press were “great bulwarks of liberty.” It refused to add a phrase before the preamble’s “We the People” that would have made clear the government derived its power from the governed. And it removed a phrase from the Second Amendment about bearing arms that would have permitted conscientious objection to military service.

Congress eliminated two amendments. One would have required the states to abide by important parts of the Bill of Rights — jury trials, rights of conscience, free speech and press. Madison thought the states were a greater threat to people’s freedoms than was the federal government. And he was right, although it took another 140 years and another constitutional amendment before parts of the Bill of Rights were enforced against the states.

Congress sent 12 amendments to the states later in 1789. The first two were not ratified, making the third amendment the first — appropriately so because it has had the greatest impact on society. In 1791 Virginia became the 11th state to ratify the Bill of Rights and it went into effect.

Richard Henry Lee, an Anti-Federalist from Virginia, wrote “the English language had been carefully culled to find words feeble in their nature or doubtful in their meaning.” But the American people liked them.

Historian Leonard Levy wrote that “As amended the Constitution became a permanent reminder of its framers’ view that the citizen is the master of his government, not its subject. Americans understood that the individual may be free only if the government were not.”

Parchment barrier

Early on, Madison had feared the Bill of Rights would be nothing more than a parchment barrier. For a long time he was right.

As a charter of freedom, it had terrible failings:

It preserved a status quo that denied most Americans the unalienable rights promised in the Declaration of Independence.

It preserved slavery, without using the word.

It did not guarantee equality — for blacks, women or poor whites.

No one’s right to vote was protected, leaving blacks, women and poor white males mostly disenfranchised. Only about 15 percent of the population had the right to vote.

Blacks were slaves and the vote of white men in slave-holding states was magnified by three-fifths of the slaves in that state to make sure they remained slaves.

Married women did not own their own property, control their own earnings, have legal custody of their children, sign contracts or sue in court.

Abigail Adams’ entreaty to her husband John, just before the Declaration of Independence, is famous. “Remember the Ladies.” Less famous is her husband’s reply. “We know better than to repeal our Masculine system.” And they didn’t for centuries.

The right of women to vote was not added until 129 years after the Bill of Rights. The nation refused to add an Equal Rights Amendment and no woman has yet won the presidency.

Alien and Sedition Acts

Seven years after the Bill of Rights was adopted, Madison and Jefferson found the First Amendment did not even protect newspaper editors who supported their party, and that the Sedition law made it illegal to criticize the president.

The United States was in a cold war with Napoleon’s France. President John Adams and his Federalist Party supported England in its confrontation with France. Jefferson and the strong Republican press that supported his party criticized Adams and claimed he brought excessive pomp to the presidency.

Hamilton, who was on Adams’ side, accused Jefferson of subverting the government. He claimed Jefferson was an “atheist in Religion and a fanatic in politics” who sought “overthrow of the government.”

Jeffersonian newspaper editors were thrown in jail for violating the Sedition Act.

This was five years before Marbury v. Madison established the doctrine of judicial review, so the jailed editors could not argue in court that the Sedition act violated the First Amendment. Madison and Jefferson were left writing the Virginia and Kentucky resolutions complaining about the law to the states.

Jefferson ironically won the election of 1800 because of the three-fifths compromise giving the South more electoral votes. Jefferson subsequently pardoned the editors who had been jailed.

A century of dormancy

The Supreme Court confirmed in 1833 in Barron v. Baltimore that states did not have to follow the Bill of Rights. A number of states had officially established churches because they didn’t have to comply. Connecticut did not end its established church until 1818, New Hampshire 1819 and Massachusetts 1833. Many states also had laws limiting public office to Christians. And abuses by state governments were rampant.

In the 1830s, Southern governments mistreated tribes of Native Americans and forced them out of their homes and onto a deadly Trail of Tears. The Supreme Court ruled that state governments had no jurisdiction over the tribes, but the old Indian fighter in the White House, Andrew Jackson, flouted the court’s ruling.

In 1838, Gov. Lilburn Boggs of Missouri gave orders to the state militia that Mormons either be “exterminated or driven out of the state.” The Mormons were driven into Illinois where Joseph Smith, the founder was imprisoned in Carthage and then murdered in 1844.

St. Louis was anti-slavery, but people didn’t like abolitionists. Toughs from riverfront saloons chased Elijah P. Lovejoy out of St. Louis to free soil in Alton, Ill. There, in 1837, a mob killed him as he tried to protect his newspaper office. The mob threw the press into the Mississippi.

In 1847 Missouri passed a law making it illegal to teach blacks. “No persons shall keep or teach any school for the instruction of mulattos in reading or writing,” it read. A few brave teachers took skiffs into the Mississippi River to evade the law.

One of the slaves then living in St. Louis was Dred Scott. In 1846 he and his wife Harriet filed for their freedom arguing they had become free when a former owner took them to free soil. In 1850 a Missouri judge ruled in Scott’s favor, but the Missouri Supreme Court ignored its precedents and kept Scott in slavery. It was worried about the growing power of abolitionists, remarking on the nation’s “dark and fell spirit in relation to slavery.” The dark spirit the court was talking about was the nation’s growing opposition to slavery.

In the most infamous decision in the history of the U.S. Supreme Court, Chief Justice Roger Taney concluded in 1857 that blacks “are not included and were not intended to be included, under the word citizens in the Constitution.”

“We the people” did not include blacks who are so “inferior” that they had “no rights which the white man was bound to respect,” Taney wrote.

Dred Scott was the first time the Supreme Court used the Bill of Rights to declare a law unconstitutional – holding that the Missouri Compromise violated a slaveholder’s Fifth Amendment property right to own slaves. The decision was a tragic misuse of the Bill of Rights and helped lead to the Civil War.

President Abraham Lincoln ended slavery, but he also suspended civil liberties. He permitted arrests without warrants, censored telegrams and suspended the writ of habeas corpus, which requires a judge to promptly charge a person or set him free.

When Chief Justice Taney ordered Lincoln to release John Merryman, arrested by the military for Confederate sympathies, Lincoln didn’t acknowledge Taney’s order.

The United States State Department censored the press and troops shuttered newspapers that criticized the war. All told, some 20,000 people were imprisoned without trials.

The 14th Amendment

The 14th Amendment, ratified after the Civil War, had great significance for the Bill of Rights. It applied most of the Bill of Rights to the states and it barred states from taking liberty without due process of law – a provision that has come to protect individual privacy and autonomy.

The sponsors of the 14th Amendment in Congress, Rep. John A. Bingham of Ohio and Sen. Jacob M. Howard of Michigan, said the amendment was intended to apply the Bill of Rights to the states. But for decades that was not the case. It wasn’t until the 1920s that the court said the 14th Amendment applied parts of the Bill of Rights to the states. And it wasn’t until the 1960s that the court found the liberty protected by due process included private matters such as contraception, abortion and interracial marriage

None of those developments seemed likely when the Supreme Court ruled in the Slaughterhouse case of 1873 that the 14th amendment did not apply the Bill of Rights to the states.

The Louisiana Legislature, controlled by northern carpetbaggers, granted the Crescent City Slaughterhouse a 25-year monopoly on butchering livestock in New Orleans. The Butchers’ Benevolent Association said that monopoly violated its right to practice a trade in violation of the 14th amendment.

But the Supreme Court ruled that if it applied the Bill of Rights to the states, it would “constitute this court a perpetual censor upon all legislation of the States on the civil rights of their own citizens, with authority to nullify such as it did not approve.” That same year, the court also read out of the 14th Amendment its guarantee of “equal protection.”

The court backed Illinois’ decision to bar Myra Bradwell, a Chicago legal publisher, from becoming a lawyer even though she has passed the bar. “Man is, or should be, woman’s protector and defender,” wrote Justice Joseph P. Bradley. “The natural and proper timidity and delicacy which belongs to the female sex evidently unfits it for many of the occupations of civil life.”

Two years later, the court ruled unanimously that Virginian Minor of St. Louis had no 14th Amendment right to vote. “The Constitution of the United States did not confer the right to suffrage upon anyone,” wrote Chief Justice Morrison Waite.

Lochner era

In 1905 the Supreme Court finally found a group of state laws that violated the14th Amendment. But the laws it struck down intended to help workers oppressed by long hours and poor wages.

In Lochner v. New York, the Supreme Court overturned New York’s law that limited bakery workers to 10-hour days and 60-hour weeks. The court reasoned the law interfered with the right of contract, which was protected from state encroachment by the 14th Amendment.

Over time, the court threw out more than 200 state regulations for maximum hours, minimum wages and other labor protections, thus elevating the rights of the wealthy over the health and safety of individual workers.

The Supreme Court of the late 1930s, which approved New Deal legislation, also put an end to the Lochner era, which now is broadly condemned by both liberals and conservatives for judicial overreach.

War

Times of war pose the greatest threat to free speech as fear usually leads to speech restrictions. It was true in 1799 after passage of the Alien and Sedition Act. It was true during the Civil War with Lincoln’s widespread actions against civil liberties. And it has been true in the 20th and 21st centuries, from the Espionage Act of 1917 to the relocations of Japanese-Americans to relocation camps in World War II to the McCarthy Red Scare of the late 1940s and early 1950s to the actions taken by the Bush administration after 9/11.

The Espionage Act and its Sedition amendments passed at a time of fear during World War I before the Supreme Court had even begun applying the First Amendment. The Espionage Act is extremely broad and could potentially be used to prosecute journalists for divulging national defense secrets. Provisions make it a crime for those “lawfully having possession of” or “having unauthorized possession of” information relating to the national defense to willfully communicate or retain it.”

During the Senate debate, one senator pointed out that the language could cover a hypothetical Iowa farmer who disclosed the number of bushels of wheat or corn raised in that state, thus providing possibly useful information to the enemy.

If these laws mean what they say and are constitutional, press reports since World War II have been full with criminality. The front pages of the New York Times, Washington Post and Los Angeles Times arguably contain information several times a week the dissemination of which violates a literal reading of the Espionage Act. Yet no reporter or publisher has been prosecuted, even though a few have been threatened. It is the officials leaking the secrets who are prosecuted.

The Sedition Act amendments to the Espionage Act made it a crime to speak abusive language about the flag, Constitution, armed forces or government. More than 1,000 people, most pacifists, were arrested and some newspapers censored in the World War I era.

Eugene V. Debs, the Society leader who got 6 percent of the popular vote in the 1912 election, found himself in prison with a 10-year sentence. His crime: an anti-war speech likening the draft to slavery. Even though his speech would be protected today, none of the justices on the court voted then to protect it. Holmes said it had the “natural tendency and reasonably probable effect to obstruct the recruiting services.”

In another free-speech decision that same year – Schenck v. U.S., upholding the conviction of anti-draft pamphleteers – Holmes famously said that free speech was far from absolute. “The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic. The question in every case is whether the words used…are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger…”

Holmes’ opinion was criticized by a young Harvard law professor, Zechariah Chaffe Jr., who suggested to Holmes that he should have been more protective of free speech.

Possibly in reaction to Chaffee’s criticism, Holmes wrote the powerful, pro-speech dissent in Abrams v. U.S., a case in which six Russian Jewish immigrants had distributed leaflets, printed in English and Yiddish, which were thrown out of a fourth- floor factory window in New York. The leaflets criticized Wilson for acting against the Russian Revolution. Abrams, who helped print them, was sentenced to 20 years in prison.

Holmes toughened his “clear and present danger test” and said no one could think the protesters silly leaflet would have an impact. “It is only the present danger of immediate evil or an intent to bring it about that warrants Congress in setting a limit to the expression of opinion,” he wrote. “Congress certainly cannot forbid all effort to change the mind of the country. Now nobody can suppose that the surreptitious publishing of a silly leaflet by an unknown man without more, would present any immediate danger….”

All of these cases were playing out in an America where Wilson was criticizing hyphenated Americans and Attorney General Palmer’s young director of the future FBI, Hoover, was rounding up anarchists, immigrants and dissidents.

One congressionally created committee, the Committee on Public Information, removed favorable references to Germany from history texts. Another agency, the State Councils of defense, organized committees that investigated and harassed German-American shopkeepers. They even banned Bach and Beethoven at concerts.

Nebraska was one of 22 states that outlawed the teaching of German in school. It said the law was needed so “that the sunshine of American ideals will permeate” pupils’ lives.

Incorporation of Bill of Rights

In 1925, Benjamin Gitlow, a member of the Socialist Party, was prosecuted under New York’s criminal anarchy law. His crime was publishing the Left Wing Manifesto criticizing mild socialism and calling for revolutionary socialism. The Supreme Court upheld the conviction. But Holmes and Brandeis disagreed with the majority, saying Gitlow did not pose a present danger.

However, there was one positive step for the First Amendment in Gitlow. For the first time the court said the First Amendment applied to state laws. This was the beginning of the incorporation of portions of the Bill of Rights against the states. The court based this decision on the 14th Amendment’s command that states not deprive “any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law.”

Two years later Brandeis set out in the most eloquent terms, the importance of the First Amendment to democracy. Charlotte Whitney, from a well-known California family, had helped form the Communist Labor Party of America. The state claimed the party advocated the violent overthrow of the government and thus violated the state criminal syndicalism law.

While Whitney denied being involved in violence, she lost in court. But Brandeis’ opinion, joined by Holmes, is one of the great defenses of free expression. Brandeis said the founders of the nation “believed that the freedom to think as you will and to speak as you think are means indispensable to the discovery and spread of political truth…the greatest menace to freedom is an inert people…. Fear of serious injury cannot alone justify suppression of free speech and assembly. Men feared witches and burnt women. It is the function of speech to free men from the bondage of irrational fears.” For speech to be punished, Brandeis and Holmes said, it must threaten a serious evil and be an imminent danger.

During this same decade of the 1920s, a wave of Ku Klux Klan violence in the South resulted in hundreds of lynchings. The Supreme Court also upheld the forced sterilization of women considered immoral or mentally feeble under authority of Virginia’s Racial Integrity Law of 1924.

Holmes, despite his civil libertarian beliefs, wrote the opinion in the 1927 sterilization case, Buck v. Bell, justifying the forced sterilization of Carrie Buck. “Three generations of imbeciles is enough,” he wrote.

Finally, in 1931 in Near v. Minnesota, the Supreme Court for the first time threw out a state law that violated the First Amendment. Minnesota’s “gag law” gave courts the power to stop publication of a “malicious, scandalous and defamatory newspaper.”

J.M. Near’s Saturday Press in Minneapolis fit the bill. Near was anti-Semitic, anti-black, anti-labor and anti-Catholic, among other negatives. He claimed that “Jewish gangs” were running the county. The governor went to court and got an order stopping publication.

In First Amendment parlance, the injunction was a “prior restraint.” A sacred principle of the First Amendment is that the government cannot stop the presses. It can punish a publication after distribution, but not beforehand.

The protection of news organizations from prior restraints set the precedent for the Supreme Court’s rejection four decades later of President Richard M. Nixon’s attempt to block publication of the Pentagon Papers.

The year after Near, the Supreme Court went beyond the First Amendment by incorporating the Sixth amendment right to counsel against the states. It took the action in the case of the “Scottsboro Boys,” nine young black men 13 to 21 accused of raping two young white girls on a freight train passing through Scottsboro, Ala. They didn’t have a lawyer until the day of the trial, even though they faced the death penalty. And that reluctant lawyer didn’t talk to them. An all-white jury convicted and they were sentenced to death. The Supreme Court said the right to counsel applied in all capital cases. In a retrial one of the white girls admitted the boys and men had not raped them. But the new jury convicted them again, although they were not executed.

The red scare

Even though the Supreme Court had begun breathing life into the Bill of Rights, that didn’t stop the internment of 115,000 persons of Japanese descent during World War II – most American citizens. Nor did it stop a wave of redbaiting after the war.

Again it was fear of the Soviet Union, which had quickly obtained a nuclear weapon, that helped drive the campaign against leftists. President Harry S Truman implemented a loyalty policy that resulted in 7,000 resignations. The Supreme Court upheld a provision of the Taft-Hartley Act requiring union officers to swear they were not communists. The court also upheld the Smith Act, which had been used to imprison Communist Party officials for advocating overthrow of the government.

In the Smith Act decision, Dennis v. U.S., the court said the country did not have to “wait until the putsch is about to occur” before acting.

Meanwhile, Sen. Joseph McCarthy, R-Wis., was destroying careers and spreading fear through Washington and Hollywood with unsubstantiated claims that thousands of communists had infiltrated the Army, State Department and other parts of the government. Leading actors, directors and screen writers were blacklisted in Hollywood and could not find work.

In 1954 the Senate censured McCarthy. The press, especially CBS’s Edward R. Murrow, played a major role in exposing his demagoguery. Fear of communists in government eased and by 1957 the court had stepped back from Dennis, ruling that second-tier Communist Party officials could not be jailed. The court ruled that advocating the violent overthrow of the government is different from planning an actual revolution.

The Warren Court

Chief Justice Earl Warren’s court was now in full swing, bringing about the most rapid expansion of rights in history in the years after its momentous Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954 overturned segregation of public schools. In a little more than a decade, the Warren Court:

- Protected the press from libel laws, making it hard for public officials and figures to win. The press needed breathing room to make mistakes, the court said in New York Times v. Sullivan.

- Invalidated prior restraint against publication of the Pentagon Papers, the secret history of the Vietnam War.

- Declared a student does not lose First Amendment rights at the schoolhouse gate, backing the right of Mary Beth Tinker to wear an armband protesting the Vietnam War.

- Upheld in Brandenburg v. Ohio the First Amendment right to hateful speech, such as Nazi and KKK protests, unless it is directed at inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to produce that action.

- Protected vulgar speech in California v. Cohen, where a man wore a jacket through a courthouse bearing “Fuck the draft. Justice John Marshall Harlan wrote, “one man’s profanity is another man’s lyric.”

- Protected the right to keep pornography in one’s home.

- Barred state-sponsored prayers in the public schools and threw out laws that banned teaching evolution.

- Recognized in Gideon v. Wainwright the Sixth Amendment right to a lawyer in state court.

- Applied the exclusionary rule to the states in Mapp v. Ohio, excluding illegally obtained evidence to force police compliance with the Fourth Amendment rules on unreasonable searches.

- Required in Miranda v. Arizona that police warn suspects of their Fifth Amendment right to remain silent and Sixth Amendment right to a lawyer.

- Recognized a right to privacy guaranteeing women access to contraceptives, a right later extended to the abortion right.

- Ruled in Loving v. Virginia the right of privacy and equality protected the interracial marriage of Mildred and Richard Loving, a decision that some 50 years later provides the basis for constitutional protection of same-sex marriage.

Even after the end of the liberal Warren Court, important civil liberties decisions continued. The court protected burning the American flag and the Hustler parody of the Rev. Jerry Falwell.

At 200, the Bill of Rights was robust. But liberals voiced fears the conservative Supreme Court would retrench. Little did they suspect that they were on the threshold of a string of decisions that would expand people’s rights in ways many liberals would not like.

No Comments