On Jan. 13 1988 the U.S. Supreme Court announced a devastating blow to student speech and the student press when it approved the authority of the principal of Hazelwood East High School to remove controversial stories about teen pregnancy and divorce from the school newspaper.

The court’s decision in Hazelwood vs. Kuhlmeier was one of the most far-reaching decisions restricting free speech and has continued to restrict student speech into the 21st century.

Even as the Supreme Court has recognized expanded free speech rights for corporations, makers of violent video games and fundamentalist picketers at veterans’ funerals, it has continued to limit the free speech rights of students in the public schools.

With today’s social media, Hazelwood’s restrictions on student speech are following students back to their homes. Some judges say principals can punish students who write nasty comments or parodies on the home computer, if the comments disrupt the school.

Gregory P. Magarian, professor at Washington University law school, has said Hazelwood “remains a very important speech-restrictive decision. Hazelwood represents perhaps the most important instance of the court’s steady retreat from protecting students’ free speech rights.”

Last minute decision

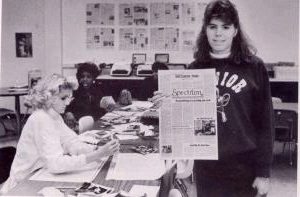

The Hazelwood East case began at the end of the school year in 1983 when the Journalism II class, which produced the Spectrum, compiled two full pages of stories under the headline: ‘’Pressure describes it all for today’s teen-agers. Pregnancy affects many teens each year.”

Principal Robert Reynolds objected to two of the six articles. One was an account of three Hazelwood East students who had become pregnant. The article made references to birth control and sexual activity and reflected the positive attitude of the girls toward their pregnancies.

The account of one of the girls, identified as Patti, read this way: ‘I didn’t think it could happen to me… I think Steven my boyfriend was more scared than me. He was away at college and when he came home we cried together and then accepted it. I want to say to others that it isn’t easy and requires a strong, willing person to handle it…Lastly, be careful because the pill doesn’t always work. I know because it didn’t work for me…I have no regrets. We love our baby more than anything in the world.’’

The other article Reynolds flagged was about students whose parents were divorced. One student complained that her father was often absent, “out late playing cards with the guys.” Another revealed, ‘’My father was an alcoholic, and he always came home drunk, and my mom really couldn’ t stand it any longer.’’ A third said, ‘’My dad didn’t make any money so my mother divorced him.’’

The names of the pregnant girls had been changed, but Reynolds was concerned that they could be identified from other information in the articles.

The Spectrum planned to delete the name of the student in the divorce article, but the real name was on the proof read by Reynolds. Reynolds thought it unfair that the father did not have a chance to respond. The principal ordered the two pages removed from the Spectrum, excising four unobjectionable articles along with the two controversial ones.

Three students, led by Cathy Kuhlmeier, challenged Reynolds’ action. With the help of the American Civil Liberties Union of Eastern Missouri, the students won in the federal appeals court in St. Louis. But the lawyers handling the case botched the argument in the U.S. Supreme Court, according to the recollections of former ACLU leaders.

The late Fred Epstein, past president of the ACLU, put it bluntly: “As I recall, Hazelwood was argued by a couple of incompetent lawyers who would accept no advice from the ACLU or other lawyers who had Supreme Court experience.”

Justice Byron White wrote the decision upholding the principal’s action. White was the author of a number of other anti-press decisions including Branzburg v. Hayes in 1972 refusing to recognize a First Amendment right of journalists to protect confidential sources and Stanford Daily v. Zurcher in 1978 approving a police search of a student newspaper darkroom to find incriminating photos of a violent protest.

In Hazelwood, White wrote the 5-3 majority opinion in which he said that high school newspapers were part of the school curriculum, not public forums for the exercise of free speech.

“Educators do not offend the First Amendment by exercising editorial control over the style and content of student speech in school-sponsored expressive activities so long as their actions are reasonably related to legitimate pedagogical concerns,” White said.

In a sharp dissent, Justice William J. Brennan Jr. said, ‘’The mere fact of school sponsorship does not…license…thought control in the high school…The young men and women of Hazelwood East expected a civics lesson, but not the one the court teaches them today.”

Cathy Kuhlmeier Frey, who now lives in southwest Missouri continues to see things differently from Reynolds.

At a forum on student speech around the 25th anniversary of the decision, Education Week described a tense exchange. “I was so angry because we had worked so hard” on those articles, Ms. Frey said, as she and Mr. Reynolds sparred over the details of the controversy. I stood up for what I believed in. That has molded me into someone who is not afraid to speak up.”

In an interview with the Freedom Forum a decade ago, Kuhlmeier recalled a girl coming up to her at a symposium on the case and calling her a “freedom fighter” while asking for her autograph.

“I never thought of myself as a freedom fighter,” she said, “but I guess I did at least try to make a difference. Students don’t have enough First Amendment freedoms. There are a lot of very intelligent kids out there and we should listen to them more. Maybe if we did the world would be a better place.”

Mary Beth Tinker’s armband

The high water mark for student free speech had occurred two decades earlier. It was 1969 and the end of the Warren Court’s broad expansion of rights.

In Tinker v. Des Moines the justices boldly proclaimed that public school students did not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.”

Early in the Vietnam War, seven young school children in Des Moines decided to wear black armbands to school to protest the Vietnam War. This was long before anti-war protests had begun the grip the nation’s campuses.

Four of the children lived in the home of the Rev. Leonard Tinker, a local Methodist minister and member of the American Friends Service Committee. They were Paul, who was eight and in second grade, Hope, 11 in fifth grade, Mary Beth, 13, at Warren G. Harding Middle School and John, 16, at Theodore Roosevelt High School.

The Tinkers recalled that their parents had been involved in civil rights and anti-war demonstrations as long as they could remember. John said in a court statement the idea was to support a Christmas season call to remember the dead in Vietnam and hope for peace. The local school board heard about the planned protest and passed a preemptive ban.

When children got to school, administrators ordered them to remove the armbands. Counselors told one of the students none would never get into college because colleges would not accept protesters. Others accused the children and families of being communists. Someone threw red paint at their house and car.

When the children refused to remove the armbands, the schools sent them home. After Christmas vacation, the students returned without the armbands but several wore black clothing for the rest of the school year to remind the school of their protest. They also went to court.

Justice Abe Fortas, in one of his last opinions, wrote as if it was self-evident that students had First Amendment rights at schools. “It can hardly be argued,” he wrote, “that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.”

Fortas based that conclusion on two important liberty decisions from the first half of the 20th century in which the court struck down laws against teaching German and against sending children to parochial schools.

In addition, Fortas pointed to the famous 1943 decision in West Virginia v. Barnette in which the court eloquently upheld the right of students to refuse to salute the flag based on religious scruples about worshiping graven images.

Fortas held that Des Moines school officials had to show “more than a mere desire to avoid the discomfort and unpleasantness that always accompany an unpopular viewpoint.” A school board would have to show that the “forbidden conduct would ‘materially and substantially interfere with the requirements of appropriate discipline in the operation of the school.’”

That did not exist in the Tinker case, Fortas wrote. He said, “in our system, undifferentiated fear or apprehension of disturbance is not enough to overcome the right to freedom of expression. Any departure from absolute regimentation may cause trouble. Any variation from the majority’s opinion may inspire fear. Any word spoken, in class, in the lunchroom, or on the campus, that deviates from the views of another person may start an argument or cause a disturbance. But our Constitution says we must take this risk… and our history says that it is this sort of hazardous freedom – this kind of openness – that is the basis of our national strength and of the independence and vigor of Americans who grow up and live in this relatively permissive, often disputatious, society.”

The notion that students are clothed with First Amendment rights in school was not self-evident to some other justices. By the time the decision was announced in 1969, it reflected the divide in society over the Vietnam War and the notion that the younger generation of protesters had grown up in a permissive atmosphere.

Even Justice Hugo Black, the First Amendment absolutist, argued that the First Amendment had nothing to do with student speech at schools. He ridiculed the court’s decision to protect the right of students to express their political views “from kindergarten through high school.”

Black concluded with a warning that reflected society’s backlash against young protesters. “If the time has come when pupils of state-supported schools, kindergartens, grammar schools, or high schools, can defy and flout orders of school officials to keep their minds on their own schoolwork, it is the beginning of a new revolutionary era of permissiveness in this country fostered by the judiciary.”

Mizzou journalism student expelled

The little Tinker children’s arm bands were tame in contrast to the content of the Columbia Free Press Underground, the newspaper that Barbara Papish distributed as a journalism graduate student at the University of Missouri.

The court described the magazine this way: “First, on the front cover the publishers had reproduced a political cartoon…depicting policemen raping the Statue of Liberty and the Goddess of Justice. The caption under the cartoon read: ‘… With Liberty and Justice for All.’ Secondly, the issue contained an article entitled ‘M———f——- Acquitted,’ which discussed the trial and acquittal on an assault charge of a New York City youth who was a member of an organization known as ‘Up Against the Wall, M——-f——s.’

The university expelled Papish for having failed to follow accepted standards of student conduct that included a prohibition on indecent conduct or speech.

But in 1973 the Supreme Court disagreed. It acknowledged “a state university’s undoubted prerogative to enforce reasonable rules governing student conduct,” but pointed to Tinker for the proposition that “state colleges and universities are not enclaves immune from the sweep of the First Amendment.”

It added that “the mere dissemination of ideas—no matter how offensive to good taste—on a state university campus may not be shut off in the name alone of ‘conventions of decency.’”

Papish never returned to Mizzou. She lived in Beverly, Mass. with her husband until she died in 2013 after a career as a technical writer and advocate of social justice. Her obituary began with the case she had won before the Supreme Court.

Conservative court arrives

Matthew N. Fraser was a student at Bethel High School in Pierce County, Washington. He delivered a nominating speech at a school assembly in which he referred to his candidate in what Chief Justice Burger referred to “an elaborate, graphic, and explicit sexual metaphor.”

Here’s part of Fraser’s speech on behalf of his friend:

“’I know a man who is firm — he’s firm in his pants, he’s firm in his shirt, his character is firm — but most … of all, his belief in you, the students of Bethel, is firm.

“’Jeff Kuhlman is a man who takes his point and pounds it in. If necessary, he’ll take an issue and nail it to the wall… So vote for Jeff for A. S. B. vice-president — he’ll never come between you and the best our high school can be.’”

According to the court record, some students hooted and yelled; some graphically simulated the sexual activities. Other students appeared to be bewildered and embarrassed.”

An appeals court had ruled in favor of Fraser, but the Supreme Court said the appeals court had not appreciated the “marked distinction” between the “sexual content of (Fraser’s) speech” as opposed to the careful expression of a political view in Tinker.

Even Justice Brennan, the court’s strongest First Amendment advocate, agreed that the public schools could intervene to teach Fraser more persuasive speech.

Hazelwood v Tinker

The speech in the Hazelwood school newspaper case was far more respectful than that used by Bethel or Papish.

But Justice White pointed to important differences between the speech protected in Tinker and Papish. Tinker involved a student expressing her views. And Papish was distributing an underground newspaper.

Neither Tinker’s armband nor Papish’s underground newspaper were the expression of a school-sponsored activity where the speech is attributed to the school. Hazelwood’s school newspaper was an official school activity.

Alan J. Howard, an emeritus professor at Saint Louis University Law School, explaindc, “The court recognized a distinction between kids at school and kids in school.” he says. “So the court found that students (even those too young to vote) are still citizens and when at school in their capacity as citizens can express their views on matters of public concern – in Tinker’s case express opposition to a war. So when walking in the halls from one class to another class, or playing outside at recess, or eating lunch in the cafeteria the school can’t punish kids talking to other kids about political issues — even if school officials don’t like what the students are saying or just don’t want kids expressing views on controversial topics.

“Hazelwood was not a case where the school officials were seeking to suppress student/citizenship speech that occurred at school. Rather it was a case where school officials were engaged in ‘teaching’ kids in their capacity as students — in this setting the school was playing the role of educator, not sovereign, and the kids were playing the role of student, not citizen.”

War on drugs trumps speech

In the years after the Hazelwood decision, free speech advocates moved to pass anti-Hazelwood laws to give student journalists broader free-speech rights. Some states have extended broader rights to both high school and college students. Illinois recently joined California, Oregon, North Dakota and Delaware in this group. States with broader high school rights are Colorado, Kansas, Iowa, Arkansas, Pennsylvania and Massachusetts.

In the years since Hazelwood, the Supreme Court has continued to limit student speech. In Morse v. Frederick – the 2007 “Bong hits 4 Jesus case” – the court ruled that a school principal could reach just outside of the school gates to discipline a wayward student.

Joseph Frederick says he wanted to get on TV when the Olympic torch parade passed his Juneau, Alaska high school. When students were dismissed from class to attend a rally as the torch passed, Frederick went home to get his Bong Hits banner.

He and snowball-throwing friends unfurled the 14-foot banner and held it in a way that the media and other students across the street on school grounds could see it.

Principal Deborah Morse saw him, took him into her office, and suspended him for what she saw as a pro-drug message. Frederick’s argument to Morse about the Bill of Rights was to no avail.

In court, Frederick argued his speech was not on school premises and it was not made in the name of the school because it was not part of a school-sponsored program, such as the newspaper in Hazelwood. He also said that he didn’t intend a pro-drug message but had chosen the goofy banner to attract the TV cameras.

In a narrow decision, Chief Justice John G. Roberts supported the principal. He pointed to Fraser’s sexually charged nomination speech in the 1980s for the proposition that “the constitutional rights of students in public school are not automatically coextensive with the rights of adults in other settings.”

In other words, students don’t lose their free speech rights at the schoolhouse gate, but neither do they take all of their rights into school.

Had Fraser given his speech outside of the school setting at a public meeting, his speech would have been protected, Roberts wrote. Similarly, if Frederick’s speech had been outside of school, it would have be protected.

Roberts rejected Frederick’s claim that this was not school speech. He pointed out that the assembly occurred during the school hours, that it was sanctioned by the principal as a class trip and that teachers were interspersed among students enforcing school rules. The high school band and cheerleaders performed. Also Frederick was standing among other students and facing his banner toward the school.

Although Roberts acknowledged that Frederick’s message could be viewed as political, nonsensical and even humorous, the principal was within her rights to see it as a pro-drug message violating school policy.

The court previously has cut back student rights as part of the fight against drugs.

In 1985 in TLO v. New Jersey, the court approved a search of a school locker for drugs based on reasonable suspicion, requiring less evidence than probable cause. The court also has approved public school policies requiring student leaders to take mandatory drug tests.

So the war on drugs trump student rights in close cases.

Internet speech from the home

The big unanswered question is whether schools can discipline students for gross, disrespectful and potentially disruptive comments made on the home computer. The court has dodged the issue.

One case it turned down involved Avery Doninger, a high school student disciplined for calling administrators “douchebags” on her blog written from home. Doninger, a student leader, was angry that the administration had canceled Jamfest, an annual event at the school. She wrote the blog to mobilize a letter-writing campaign to overturn the cancellation.

Another tricky area of student speech outside the classroom is cyber-bullying.

Megan Meier, a 14-year-old from St. Charles, Mo., hung herself in 2006 after reading a fake MySpace post from a person she thought was a boy her age. The fictional boy had first expressed admiration for her but then messaged, “The world would be a better place without you.” She hung herself.

The posting actually had been written by a mother in the neighborhood. The mother was prosecuted under federal hacking laws and eventually freed because the hacking laws were too vague and an infringement on the First Amendment.

Missouri and many other states passed cyber-bullying laws to make this kind of cyber-harassment illegal. But those laws haven’t been tested in the Supreme Court.

Magarian, the Washington University expert on free speech, says that the Supreme Court’s weaker protection of free student expression is consistent with weak support on the court for the press in general.

“The idea of press rights, as a specific, separate category of free speech rights, has all but died on the vine,” he says. “That has more than anything else to do with changes in media economics and technology. But even before the Internet, the court had largely embraced an attitude toward press rights that was indifferent at best. Hazelwood is part of that.”

No Comments